There are many carved freestone effigies in churches all over the country, and in the majority of cases these are of either knights in armour or senior ranks of the clergy. Pembridge is different.

We have Nicholas Gour, Sergeant-at-law with presumably his wife and his son, John Gour and wife, a steward in the employ of the Mortimer family and probably an apprentice-at-law, the level below a sergeant.

According to “English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages” by Nigel Saul they are Nicholas Gour and his son John. One was a Sergeant-at-Law and the other was a steward for the Mortimer Family. Sergeants-at-Law were an elite order of Lawyers who had exclusive privilege of arguing before the Court of Common pleas and the Court of the Kings Bench. For six centuries, starting in the 1300’s, they ranked above all other lawyers in the kingdom. Only twelve hundred men were ever promoted to the dignity of Sergeant, the last dying in 1921.

We are extremely fortunate in many ways that these have survived, virtually intact since their creation, probably in the late thirteen hundreds. Presumably they were originally painted in the rich colours of the day. In fact the whole church would have been extremely colourful with all the walls painted and in the stained glass the arms of Mortimer, Geneville, Grandison, France and England.

We haven’t been able to identify where they were carved; the main centres for this type of work were in London although there was a provincial industry. Many stonemasons working on cathedrals and church buildings would add to their living by producing carvings as well. Wherever they were carved they would have been very expensive; both to produce and to transport.

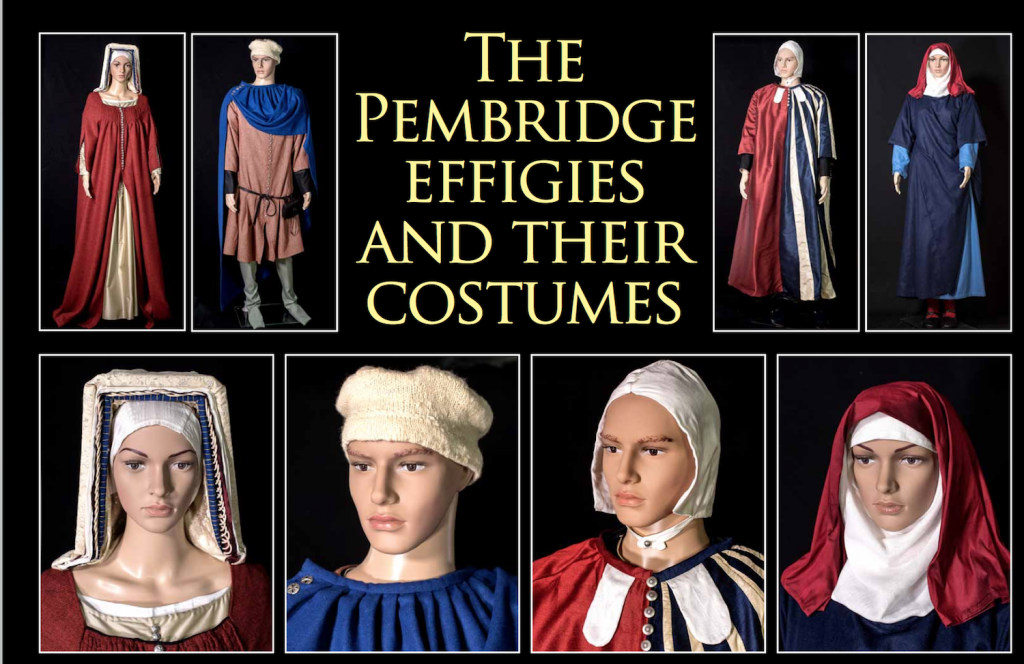

As any student of medieval costume will realise we are also fortunate in that the styles of dress of each set of effigies is quite different and yet they are only a generation apart. Nicholas and wife are wearing long flowing gowns, coif and wimple, while the next generation, John and wife are in tightly buttoned, close fitting gowns and far more elaborate hats. Had they been carved a generation earlier there would have been very little difference – rather like the suits of the 1940’s and 1950’s being very similar but giving way to the denim and “flower power” of the 1960’s and 70’s. One theory for this change is that the tailors had developed the technique of cutting on the bias, allowing the material to fit the body better – technique widely used by Coco Chanel.

Nicholas and John are accompanied by two ladies who we assume are their wives.

The costumes

Recreation of Mediaeval Costumes

A chance meeting with the author and medieval clothing specialist Sarah Thursfield at the Leominster Medieval Pageant in the summer of 2015 led to the suggestion that re-creating the costumes worn by the effigies would be a useful exercise. This would lead to a better understanding of how people would have dressed in Pembridge in the fourteenth century while, at the same time, provide an added benefit to tourists and historians alike and help to keep Pembridge and St Mary’s church on the map.

These were completed in 2017 and can be seen in St Mary’s Church, Pembridge. A brochure is available from the church which details the project and the later work to recreate the costumes from a 1301 wedding in Pembridge.

The history of the effigies

We have a number of different descriptions for these figures dating back several centuries and, while there are variations in the descriptions, they all suggest that these are high status individuals.

The earliest description is from Richard Symonds, a trooper in the English Civil War who visited Pembridge in 1645 and, fortunately for us, kept a diary.

He writes:-

South Window, chancel.

Under this window, upon a low altar tombes of playne stone, lye the four bodies of men and their wives, ad hayne formam, old:

This is observable, for never afore have I seene a thing of that age (unless a churchman) without armor.

The other is a fashioned habitt, not so observable, in a kind of a long robe, without anything on his head.

The inhabitants say they were in memory of the Gowres of Worcestershire.

Thirty years later, in 1675, Thomas Blount wrote:

PEMBRIDGE:

“Within the church are two chapels or chancels; one called Marston Chapel and the other belongs to the Lochards. In the first are two ancient monuments of man and wife (drawn by Dingley in p. cclii.) said to be Gours, former lords of of Marston, which now belongs to Monington of Sarnesfield. In the window, a lyon rampany gules. Williams. Monington.”

It is interesting to note that Symonds saw them under the south window of the chancel while Blount saw them in what is now the north transept.

The tombs were also described in some detail by Mary Langston in 1934.

On the north side of the chancel are four effigies, two men and two women on an altar table, said in Blount’s MS, to belong to the Gours, Lords of Marston, which effigies were, in 1675, in the north transept, or Marston Chapel; from there they were moved to the south side of the chancel, then to the west end of the north aisle, and in 1909 were placed in their present position, as there the original foundation of the monument was found. Two of them represent a man and woman in the dress of the fourteenth century , and as at that date it was very unusual for a man of position to be depicted in civilian dress, not in armour, this effigy is of exceptional interest. The Rev. J. B. Hewitt, in an article contributed to the Woolhope Transactions in 1901, thus describes them:-

“He (the man) wears a short tunic with sleeves laced close round the wrists, a coat with somewhat shorter sleeve, and a long flowing cloak fastened to the right shoulder, and thrown back. Low shoes fastened across the instep with a narrow strap. His only weapon is a short sword, hanging from a jewelled belt. He wears a moustache and divided beard . . . . The dress of the lady beside him, evidently his wife, shows the sleeve of the garment buttoned closely to the arm, that the outer one is lying open, but having buttons and button-holes throughout the length. She wears the square headress of the period, and the veil round the throat and chin. Another effigy is that of a Nun, which being the same mourning habit, was sometimes given to a widow dying within a year of her husband, so it is possible that the popular idea of these figures may be so far right that this lady was the second wife of Gour, having survived him a few months.” “The fourth effigy is that of a priest in the robes of on of canonical rank. He wears the ‘Toga talaris” or ancient cassock, the skirt not being visible, but the sleeves appearing laced tightly to the wrist. Over this is the Alb with its close fitting sleeves shorter than those of the cassock , and over all the short tippet with bands, but showing no sign of fur. Upon the head is the close fitting cap fastened under the chin. The upper lip bears the moustache, but the chin is clean shaven. Upon the right side is what appears to be a cord, passing through the robes, and carrying some article, which has unfortunately been broken away. This figure measures only 5 ft. 4 in. It s interesting to find that one Thomas de Penebrugge (the old name for Pembridge) was Prebendary of Bartonsham, and treasurer of Hereford Cathedral in 1317. This date would seem to throw a difficulty in the way of assigning the effigy in question to him, as the church was probably not built till towards the end of the fourteenth century; but here again the existence of the earlier building may give a solution to the difficulty. If the effigy is that of Thomas de Penebugge the cord at the side may have the keys, or possibly the purse to signify his office, and it may well have been removed from the earlier Church to the present one, were a sepulchral arch (now empty) in the south wall of the chancel was probably its resting place.”

Nicholas Gour

So looking at them in a little more detail, first, what is a Sergeant-at-Law?

Sometimes called “King’s Sergeants” or “The Order of the Coif” these were highly respected legal experts who’s business was to act as legal advisors to the Crown; in the period we are looking at that would have been Edward III and Richard II. Nicholas Gour was, we believe, a Yorkshireman and was created a Sergeant in 1354. He was CJJB Ireland in 1346 and Commissioner until 1358.

In the six centuries after 1300 only about 1,000 advocates were admitted to the order. In former centuries they were the elite of the English bar and occupied a position more exclusive than that of Queens Council today. The customs of the order included the wearing of distinctive parti-coloured robes, a white silk coif, the giving of gold in the form of rings engraved with mottoes and the hosting of a feast.

The feast could also be expensive and, in the early days it would last a week and the expense of this was greater than that of the rings.

“The Sergeants received their guests with ancient ritual and dined themselves in silence, a yard apart, with numerous servants attendant.”

In 1540 the sergeants obtained the Kings’ permission to curtail the proceedings to a single day. However, dinner this “day” included over 25 deer, 44 swans, 36 herons, 132 rabbits, 132 woodcocks, 540 larks and 240 jellies, eked out with sturgeon, pheasant, turkey, crane, brawn, quince pies, marchpanes and custards and washed down with over 175 gallons of claret wine.

We can assume that with this amount of outlay their future role was going to be highly profitable.

The meaning of the clothes

The distinctive badge of office of the Sergeant-at-Law is the white silk Coif and the parti-coloured gown. When they were admitted to the order the ceremony included the following words:-

“You have a quoife as an helmet, to make you remember to be pure and unspotted, white and innocent, and yett an helmet to be strong and bould in your client’s case to speake the law and to be constant and firme for your clyent. You have a garment of two colours, to teach you to have care aswell for the poore as rich. You have a tabert, an ancient garment, close before, to teach you to be seacrett and to keep councell. It has two toungs of like greatness and proportion, not one bigger than the other, to put you in mynde that you have the same tounge and speak as well for the poore as for rich clyent. You have scarlett, a severe and judiciall colour. You give gold, the best of all mettalls, to put you in mynd that you must be liberal accordinge to your abilities”

John Gour – the son and a steward to the powerful Mortimer family

Extracts from English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages, History and Representation by Nigel Saul

“The man commemorated by the latter of the two effigies at Pembridge (Heref.) was again someone with strong magnate connections. He was almost certainly John Gour, a scion of a legal dynasty and an esquire who held a manor in the parish. From the 1350’s until his death in the late 1370’s Gour was active in the service of the Mortimer earls of Marche, the most important landowning family in the central Marches, for most of that time serving as a Steward. In 1360, when Earl Roger died, he was appointed keeper of the Mortimer estates in the Marches for the duration of the minority which followed. His close connection with the Mortimers ensured him frequent appointment to public office in Herefordshire.

He is first found associated with Roger Mortimer on a commission of 1351. He is found as a witness to Mortimer charters and was also and executor to the Earls will.

From 1356 until his death he served as a justice of the peace in the county, and from 1369 as a JP in Shropshire. In 1360 he was named keeper of the temporalities of the bishopric of Hereford following the death of Bishop Trilleck. It is evident from his appointments that he must have received a training in the law, perhaps through acting for his father who was a sergeant. On his tomb he is shown wearing a tall headpiece very similar to the puffed hat later worn by the apprentices; it is possible that his occupational standing corresponded broadly to that enjoyed in the next century by men of that rank.”

So, whichever description you favour they all suggest that these are rare and interesting effigies that deserve further investigation and preservation.