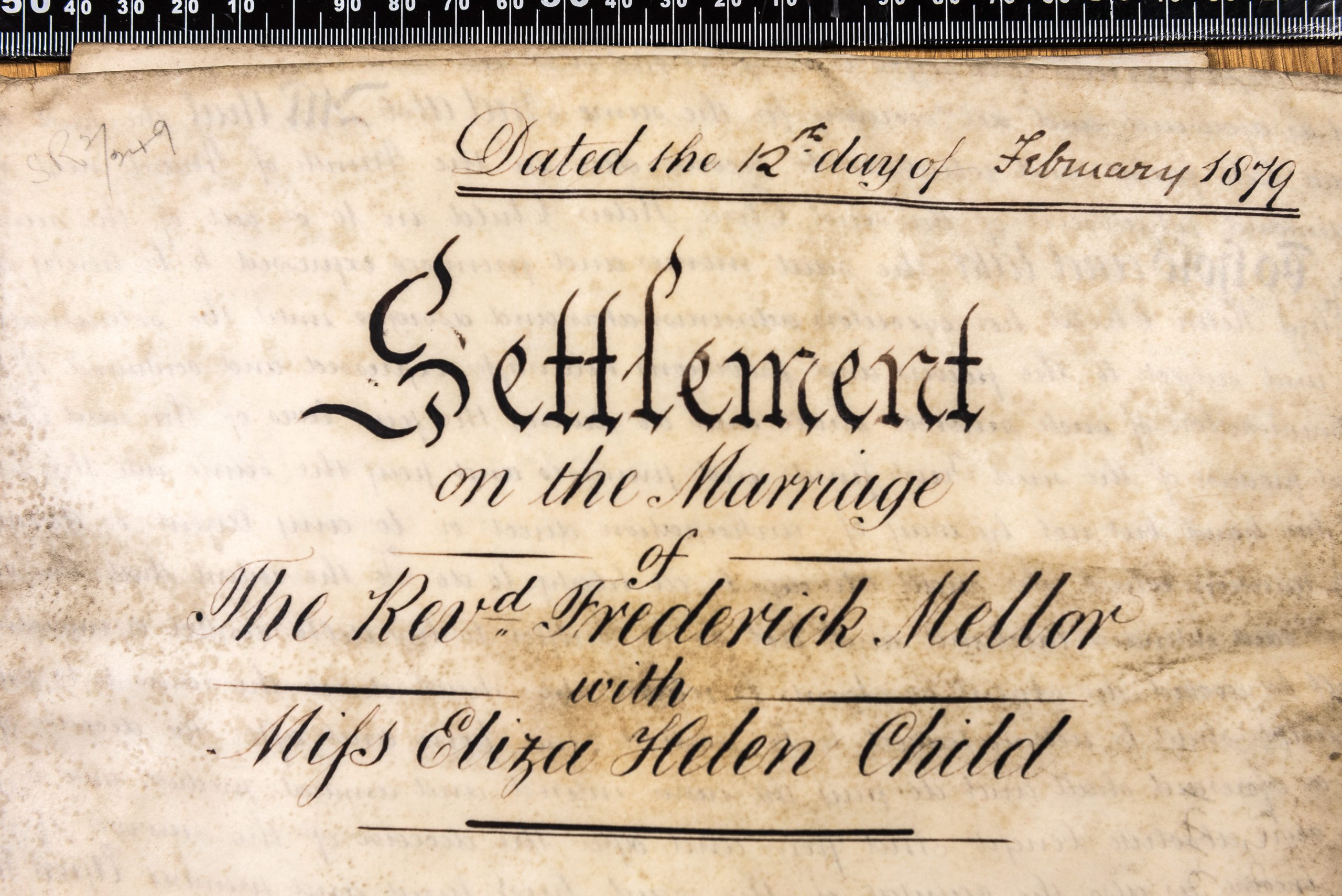

A marriage settlement is a legal document usually drawn up before a wedding, used to describe the financial arrangements between the two families. Although they are not as common a record as birth, marriage and death records, they can still tell us some interesting information about the people who lived in Pembridge. A copy of a marriage settlement from Eliza Helen Child has survived, and was very kindly lent to me by Micheal to study and write about. This document dates back to 1879 and gives a fascinating insight into the priorities of the families at the time.

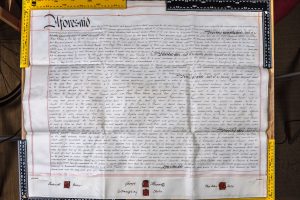

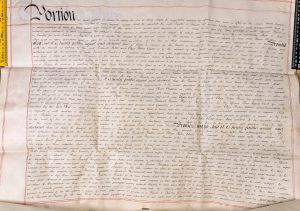

Eliza lived in Westonbury, a couple of miles outside of Pembridge, until she married, and although we don’t know much about her married life, the settlement does tell us about the financial agreement that was set up when she got married. It describes the money which will be settled on Eliza and how it is going to be managed when they are married, and what will happen if one dies, and the arrangements if they have children. This settlement was signed, sealed and delivered on the 12 February 1879. (Signed, sealed and delivered is a legal term which meant that the document was signed by all parties, sealed with red wax, and delivered, and was therefore binding on all parties).

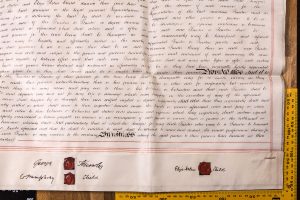

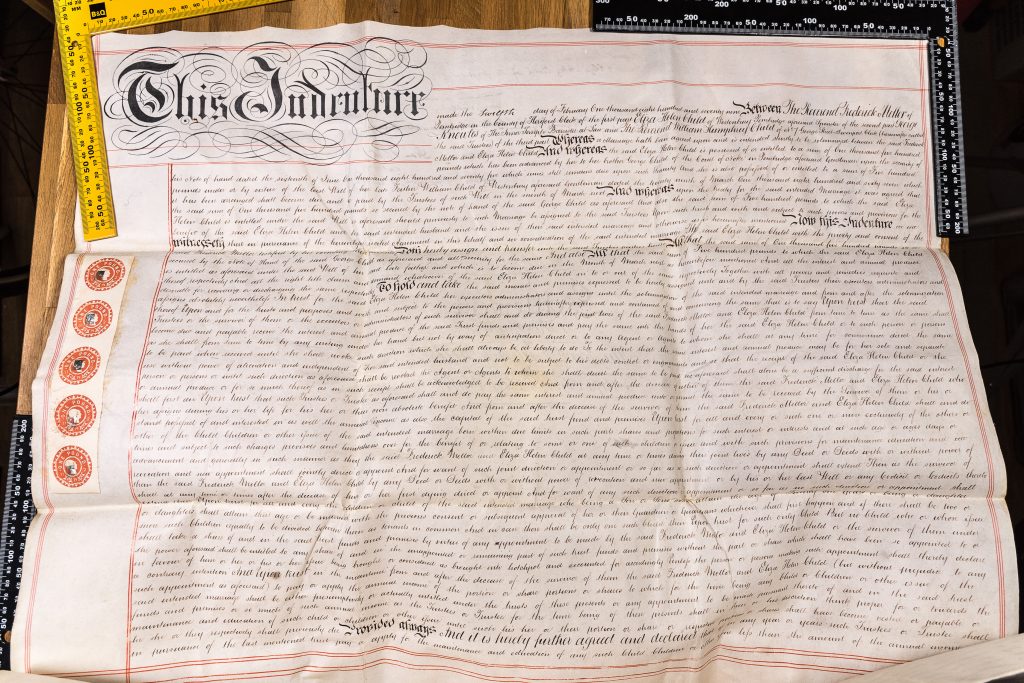

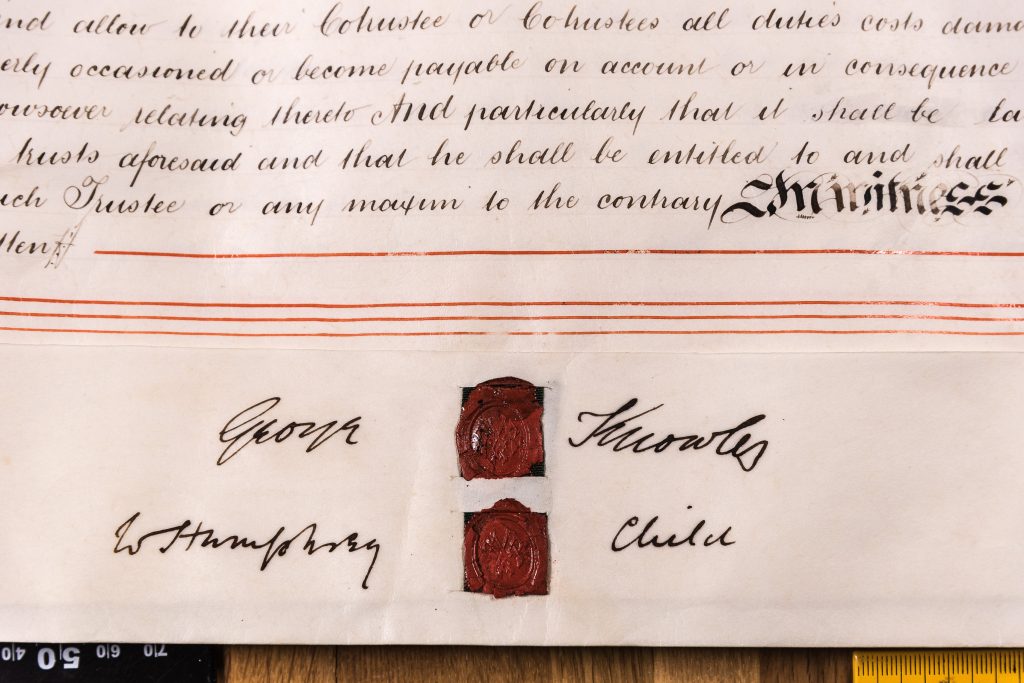

The document is between three parties, firstly, Eliza Helen Child of Westonbury, secondly her husband to be the Rev Frederick Mellor of Hereford, and the third party was the two trustees. The trustees are one of Eliza’s relatives, the Rev WIlliam Humphrey Child, Devonport, (possibly a brother) and George Knowles of the Inner Temple, barrister at law.

The marriage settlement states that Eliza is due to inherit £500 from her father’s will. Her father, William Child had died the previous year. He is buried, along with his wife, in Pembridge Churchyard. Their grave can be seen around the back of the church, towards the moated site.

Eliza is also promised £1,500 from her brother, George Child of the Court of Noke as the document goes on to explain and this money to be assigned to the trustees to manage for the benefit of Eliza and her husband, and any children that they have. The annual interest is to be given to Eliza, or a representative that she directs to collect it. There is an interesting phrase that this money is ‘for her sole and separate use without power of alienation and independent of her said intended husband and not to be subject to his debts, control or engagements.’ It appears that the intention of this document is to ensure that Eliza’s dowry was used to support her financially throughout her married life. This was at a time when married women could not own property in their own right and any money she had would have become the property of her husband when she married. This is established on the first page of the document, the remaining two pages describe what would happen in the event of the death of either Eliza or Frederick, and covering many different eventualities for children. It then goes on to talk about the trustees responsibilities as well.

It is a lengthy document, three pages of text, sewn together at the bottom. Each page is approx 28 x 22 1/2 inches and hand written. I would not like to cast aspersions on any lawyers, however reading it does lead you to wonder if the lawyer was being paid by the word as it is quite verbose in places and you get the impression that they didn’t use one word when three would do instead.

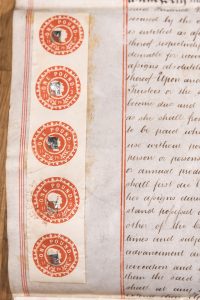

The document itself is a fascinating object in it’s own right. At the bottom of the page, all of the parties involved in the document, Eliza, her husband to be and two trustees have all signed next to a seal. The document also has a series of stamps on it, to cover the stamp duty that was payable at the time on legal documents.

But we can find out a bit more about this family from other records and get more of a picture of their life in Pembridge.

When Frederick and Eliza got married, Frederick had been the curate of Pembridge for three years. He started in the parish in 1876 and stayed here until 1891. He had studied at Cambridge University, and The Rector at the time was Rev. James Frederick Crouch, who was instituted in 1849, and was also a prebendary of Hereford, and a rural dean. The Rector received all the money from the tithes that were associated with the particular church i.e. income from land such as rent, or ten percent of crops. The curate was paid a salary by the rector to do the work of the parish.

While in Pembridge, they lived at Byletts Cottage, and Frederick can be found in the 1881 census along with Eliza, his wife and George, their son, who had the occupation of curate’s wife and curate’s son respectively. Their son was a year old at this point. Eliza was 28 and Frederick was 32. They also had two servants Elizabeth Stephens (18) and Martha E. Griffiths (14).

The next census of 1891, finds them living on Bridge Street. George is away at school, and they have a nephew staying with them and one servant, Emily E. Hill who is 15. Not recorded is their daughter, as they lost her in the intervening years. There is a gravestone in Pembridge Church which is dedicated to her.

‘In loving memory of France Mary, daughter of Frederick & Eliza Helen Mellor, who died Dec 16th 1885, aged 2 years. He shall gather the lambs with his arms and carry them in his bosom.’

This grave is found near the back of the church, by the path leading to the moated site. Although described in a survey of 2009 of being a cross on a 3 stepped pedestal, it has unfortunately lost it’s cross, and only two of the steps of the pedestal can be easily seen. There is a sandstone cross leaning up against a nearby gravestone which may be the missing one from this. The grave is near that of Eliza’s parents, her father William, who died a year in 1878, a year before her marriage, and her mother, also called Eliza who died in 1890.

1911 finds them in Dilwyn, along with their 19 year old daughter, Beatrice and Eliza’s sister, also called Beatrice. They have two servants at this time. Mabel Alice Addis who is the cook, aged 15 and Sarah Irene Lane, who is the housemaid (and also 15). Eliza passed away in September 1923. In 1924 Frederick retired to Eardisland until his death in 1930.